Learn about old village life in Rhossili and Gower here.

Over My Shoulder

From the Gower Society Journal 1949.

It’s funny how some little things start us thinking back, and comparing today with yesterday. I was watching my children eating their breakfast the other morning, one was enjoying a banana, the other a peach. A banana from the Canaries, I thought – a peach, perhaps from Italy. In remote Gower! In ten minutes, by the electric clock, the bus will pick them up at the door and whisk them away to a school twenty miles off, dressed in outfits that would have cost a twelve score bacon pig in my school days.

I was one of a family of seven, all born in the “cupboard” bed, that wooden structure that adorned the corner of most farm houses and country cottages. It had no window, but sliding doors, to shut out the view of any visitors who called after bedtime. It was about three feet off the floor and entered by using the fireside settle as a step. (Some people used the recess underneath for storing coal.) To sleep in the cupboard beds with my parents, in spite of the lack of ventilation and light, was a rare treat for me – if one managed to wake around supper time, there was a chance of a cup of bread and milk or a drink of tea out of mother’s cup.

We had a small farm and ever since I can remember I had to get up at seven o’ clock to feed the stock – “things,” as we always used to call them, before going to school. I was a martyr to chilblains, and oh, the agony of trying to get tender feet into stiff hobnailed boots that had been wet the day before and put on the pentan to dry; and, with sleepy eyes, holding the end of the leather lace in the candle flame to make it rigid enough to find the eyelet holes.

My life was typical of most village boys, hard but happy. When I was twelve I used to work for a neighbouring farmer, before and after school, Saturdays and Sundays, for the princely sum of two shillings a week. We lived as far as possible on what we produced ourselves. Our family income consisted of the sale of two fat cattle, a bacon pig, a few lambs sold in May, the wool off the sheep in June, a dozen to twenty wethers, a few eggs, a chance pound of butter, and, in the summer, an occasional lodger. Out of that we had to pay £25 a year for rent. We grew our own wheat and had it milled at the Middle Mill in Bury, the charge for milling being a percentage of the wheat. Once a week my mother baked ten big loaves in the brick oven. If we had a wet wheat harvest it affected the whole year’s supply of flour: for twelve months we would have a black ring about an inch inside the crust of every loaf. However, Lizzy the Mill was a good friend to us, she sometimes “made a mistake” and for six weeks we would eat the good wheat flour of some other farmer. We fed two bacon pigs, we sold one and eat the other. Killing the pig was a great day – the lucky boy had the bladder for a football, and then for some days, there would be chitlings, tripe and blackpot to eat. The butcher coming to cut the carcase up would always come after dark, which meant staying up late to hold the candle, while the grownups were busy salting. Many a clip on the ear I had for not holding the candle still. Another “occasion” for me was the selling of the two fat cattle in February. It was one of my most gruelling jobs of the year, starting out before daylight and driving the reluctant beasts in front of me all the way to the Gower Inn, where the butcher’s drovers would take them over, and then walking back again with my hand on the twenty four neatly wrapped-up gold sovereigns in my pocket. They once rubbed a big blister on my tender groin before I reached home. Among the jobs I disliked most was helping to thrash the corn. The contraption for doing this was very primitive: it was driven by two horses harnessed to a rotating pole; two boys had to urge these animals to walk round in a circle and keep the bewildering mass of cogs moving. This was long and tedious work.

The happy memories last longest of course. I was proud to be allowed, when a little older, to take the horse and cart to fetch coal from Llanmorlais; then there were the twice yearly trips to Swansea in the horsebrakes, starting about 5.30, walking all the hills, and arriving in Singleton St. at about 9.30, to meet the smell that came from the Old Brewery. To me, our cowstall smell was lavender compared with it! Once a year the children of the villages were the guest of Miss Talbot at Penrice. The excitement of going, playing games, picking conkers, the tea served by real butlers, my recitation, another boy’s solo, the parson’s speech of thanks, and the race home – happy but very tired; our pleasures were all as simple as that. We used to sell wild flowers to day picnickers for 2d. a bunch, and then live like Rothschilds for a fortnight on tenpence. Every Good Friday we would set fire to the gorse on the cliffs, and later our sport was boxing in the barn by candlelight. Alas, one morning I came into breakfast with a nose as big as two, and mother burned the gloves in the brick oven. I am paying today for missing that right hook. And shall I ever forget the harvest festivals, to which all the boys and maids used to tramp from miles around, and old Mr Helme’s harvest supper, with Phil Tanner singing?

In school I’m sure I was a favourite, because I was a diligent, if dull, scholar. I loved my teacher, and I believe she still has a soft spot for me, in spite of my complete failure to reach any of the heights she forecast. But I am grateful to her for teaching me all I now know of Algebra, Geometry, Latin and French prefixes.

Time gilds even the memory of ill health. I never remember a doctor calling at our house. Mother was our doctor: feet in mustard and water and goosegrease on the chest for a cold, flour and water with a pinch of saltpetre for a good sweat, your own sweaty sock around the neck for a sore throat, skin of mort (the skin off the fat of a pig’s belly) for a festered finger – and for something more serious, the village midwife, a genial old soul could be called in. Neither she nor my mother knew anything about temperatures or medicines, other than senna tea, but somehow we all survived.

I often wonder how it was all managed. A hard existence, a table full of children to feed and clothe, and to be taken to chapel twice every Sunday with a penny each for collection – where there was always one pair of adult eyes watching to see they were all put on the plate. I know I felt proud to hear our old village blacksmith tell me: “I never had to call at your house twice with my bill.”

The peach and the banana have gone. Are these children as lucky as all that? Sometimes I just don’t know.

Jack Bevan

We are grateful to the Gower Society for allowing us to reproduce this article from their 1949 journal. Special thanks to Pauline Bevan for giving us a copy of the original article written by her father in 1949.

Remembering Rhossili – A Letter from Australia

Judith Mary Jenkins has been living in Brisbane, Australia for the past 20 years or so and here she shares her memories of growing up in Rhossili.

“I thought I would just write a short note about what Rhossili was like during and after the War, when I lived at Great Pitton Farm and I used to spend all my time with my cousins, Ann and Roger Harding, and my brother Christopher, although my father died when Christopher was only 11 years old and after that he used to have to spend most of his time farming. Ann now lives in Western Australia, but Roger and Christopher are still there to keep an eye on things!

During the war there were about 200 people living in the village and I think I had been into every single house. We used to go around collecting for scrap metal etc. during the war, and we also used to get money for the National Savings stamps that we were all encouraged to buy to help the war effort.

We all went to school in Rhossili where we had two teachers; Miss Button taught the ‘little ones’ and Miss Thomas taught the ‘big ones’. Both Miss Thomas and Miss Buttton lived in the village so they knew all about us. I have to say that we had a wonderful education, and I think I learned more at Rhossili School than I did for the rest of the years that I was supposed to be learning. Miss Thomas was particularly keen on Geography and music, and I still remember all the counties in Wales although they have changed many times over the years. We had a Guide group that met in the Village Hall every Friday evening and that was such good fun. I suppose there would only have been about a dozen of us altogether and Mrs Roberts, (the mother of Dora Rosser) who lived in Harepits, was in charge. In the summer we used to go ‘tracking’ around the village, and in the winter we learned useful skills so that we could earn our badges. I was actually underage at the time that I went to the Guides but there was no Brownie group for me to join, so I went to Guides instead.

I remember that in the summer we used to go out to the Boathouse near Worms Head, and jump into the sea. When the tide was in, it must have been very deep and I don’t think I could really swim, but I must have survived, and my mother didn’t seem to worry where we were as long as we were home for our evening meal.

I think that the telephone came to the village in the 1940s. I remember that the Coastguards were Rhosilly 1, the Post Office (which was also the exchange) was Rhosilly 2, Great Pitton Farm was Rhosilly 3, Miss Thomas was Rhosilly 4, etc. And yes, we used to spell the name of the village differently in those days. After being Rhosilly 1,2 3 etc, they became Gower 501, Gower 502 etc, and then Swansea 390501, Swansea 390502 etc until they became 0792501, 0792502, and most recently 01792390501 etc.

During the war, Mansel Thomas lived in Alveley, and you may remember his widow, Gwen, who lived there until relatively recently. Mr Thomas taught German at Bishop Gore School, but his real love was writing plays, some of which were performed on Radio Wales. He wrote a lot of plays that were put on in the Village Hall, and they were wonderful. They were obviously written with the villagers in mind in terms of casting, and the plots were also related to the village. For example, one of them was about the smugglers who used to wreck ships off the coast. They were a great success and involved a lot of people in the village at a time when there was not much entertainment available. Mr Thomas used to produce them and he was an expert!

I think that most people in UK think of Australia as a land of sunshine and beaches. They are not wrong as far as the sunshine goes. But the beaches are nothing to compare with the Gower beaches with the wonderful cliffs, caves, rock pools etc. But I have such happy memories of life in the village and they will just have to suffice.”

Judith Mary Jenkins

From Rhossili Newsletter 2020 (Reproduced with permission)

Rhossili Now and Then

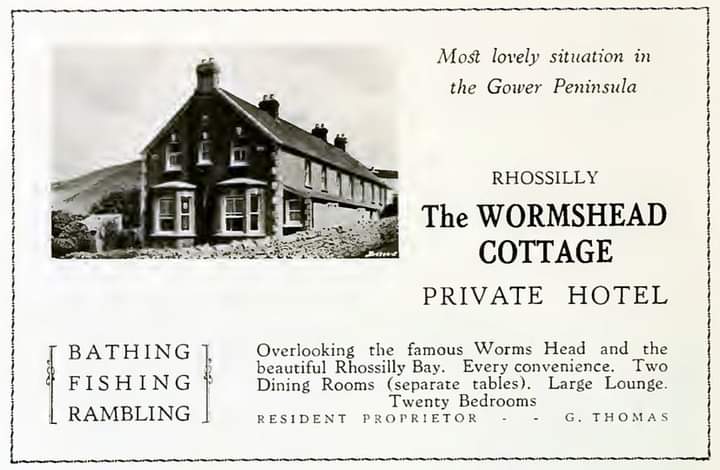

The Worm’s Head Hotel as we know it today, is very different from the row of cottages it grew from. In Jack Bevan’s book, Reminiscences of Pre-War Gower, he shows this image below of Worms Head Cottage, although it isn’t dated.

The next image from 1934 shows how it continued to grow, becoming the Wormshead Cottage Hotel.

And compare that to today!