The underlying message of this article is that ecology is unbelievably complicated and nothing is ever as simple as it seems! If you are in doubt about how to progress a nature project, it’s always worth consulting someone in the know, such as someone from your Local Nature Partnership (https://www.biodiversitywales.org.uk/Swansea)

Myth 1 Plant a tree to save the planet

There are a few caveats to this that you need to think about before planning a tree planting project. People used to think that woodland was the ultimate habitat, stretching from Lands End to John O’Groats and a red squirrel could bounce through the trees all the way without touching the ground, but this has been proved to be incorrect! The UK, including Wales, used to be a mixture of woodland, scrub and grassland, changing over time and managed by large herds of wild herbivores, such as wild cows (aurochs), wild ponies (tarpan), deer, moose, bison and boar. These would have been moved around by the large predators we used to have, including wolves, lynx and bear. Sadly we made most of these species extinct or domesticated them into the cows and ponies we know now. Native hardy breeds, such as Welsh Mountain Ponies and Welsh Black cattle, are important tools to manage the mosaic of habitats we require for a functioning ecosystem.

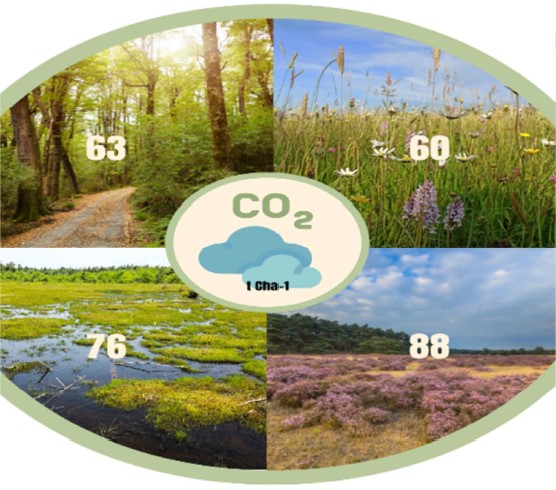

Although this diagram above picturing soil carbon is a simplification, you can see that there are other habitats that store carbon, some far better than woodland such as in the soils of heathland and bog habitats. Grassland and coastal habitats also play their parts. Most of these habitats have organic soils, i.e. soils that contain decomposed plant matter.

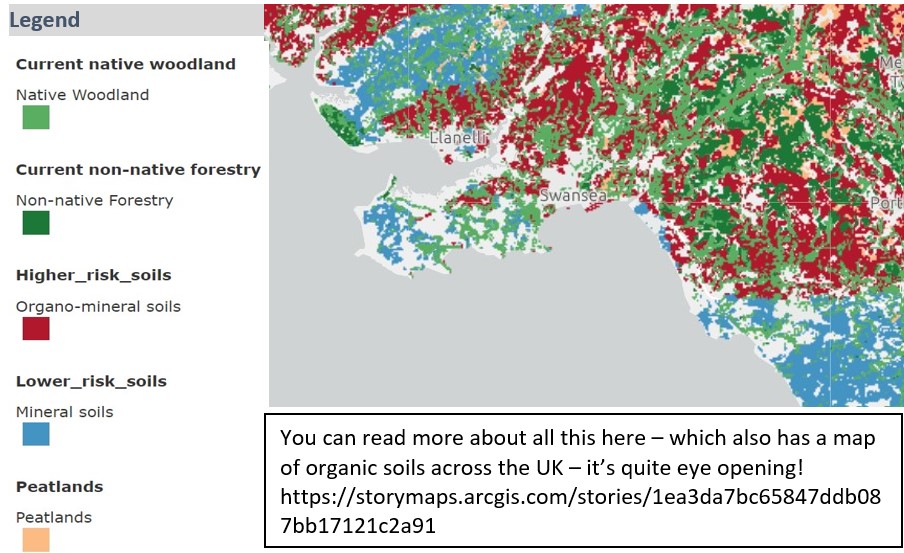

Comparison of soil types has revealed that some are more suitable for woodland expansion than others. Tree planting on organic soils with a high carbon content, such as those in our peatlands and grasslands can damage the carbon store and lead to carbon being emitted. Tree planting on organic soils will not deliver climate benefit by 2050 and may never do so on peat, so should be avoided. Tree planting on one of these habitats could have the exact opposite effect of what they are trying to achieve.

In this map of Swansea and Gower, blue indicates inorganic soils across south Gower, so in theory, tree planting here would not have a negative carbon capture effect. However, if tree planting here was to replace other habitats such as heathland, grassland or bog/ wetland (all of which occur in these blue areas), tree planting would be likely to have a negative effect. And whether the trees could survive the winds is another matter!

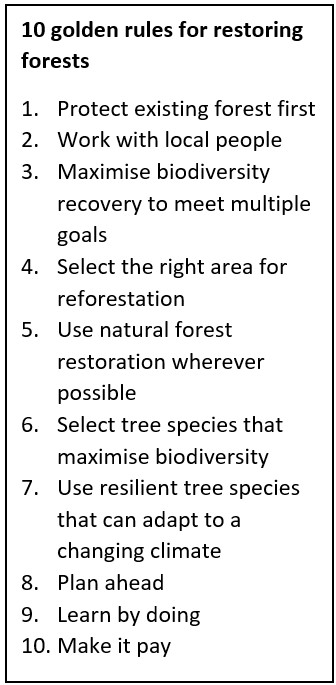

If you want to do a tree planting project, use Kew’s ten golden rules for tree planting.

One that is particularly noteworthy is number 5: Use natural regeneration wherever possible. When you think about nature conservation, in simple terms most habitats are trying to become woodland, without the natural grazing pressure of the herbivores mentioned above. So many conservationists spend time removing trees from where they are trying to establish in other vulnerable habitats, increasingly by using native grazers. You can see this in the photo, which shows willows rapidly spreading and causing a nuisance in some lovely marshy grassland, home to the endangered Marsh Fritillary butterfly.

So instead of spending a fortune on tree planting, why not make use of this?! Natural regeneration means just letting the tree stock in the local area replenish an area without any need to use carbon to transport trees across the country and cover them in plastic to help them establish. Consider trying to replicate the natural wood pasture of old times, there’s a great video about this from Knepp, here.

Another thought is rather than planting a woodland, would a hedgerow be a better way to do it?

Myth 2 Save the (Honey) Bees

One of the first things that is suggested in a community nature project is always honey bee hives and you can see why – we all know we need to save the bees – they pollinate our food and without them we simply couldn’t survive. And pretty much every campaign on the subject will feature honey, hives or a picture of a honey bee. Now honey bees are absolutely wonderful for the wax and honey they produce for us, the pollination service they provide and the wellbeing benefits of interacting with a hive and keeping bees, but if you are designing a project to help the bees in your local area, should you install a hive?

Worldwide, there is increasing concern that declines in wild pollinators may be worsened by high densities of honeybees. One honeybee hive can contain over 40,000 bees. That’s 40,000 bees introduced to an area that they wouldn’t necessarily have been naturally, placing a huge strain on the indigenous bees as they compete for food and resources. Unfortunately honey bee hives have also spread disease to wild bee populations, devastating their local populations. Introducing a hive in an area where a rare bumblebee species makes its home could spell the end of that rare bee population in that area.

There are many other actions you can take to help to save the bees, instead of introducing honey bee hives:

- Provide Bug hotels or a build a Bee Bank as explained in this PDF.

- Resist tidying (bumblebee queens and caterpillars overwinter in tussocky grass or bases of plants) and leaving a ‘wild’ area unmown over winter can help them survive the winter months.

- Equally, some species overwinter in dried stems of dead plants and clearing out your flower beds too early can lead to these species not surviving the winter. Resist the urge to tidy up over winter and leave some dead stems standing until the temperatures are consistently above 10oC in Spring. This can offer a huge boost in helping pollinators survive the winter.

Myth 3 Ivy kills trees (or does it?)

Ivy often gets the blame for strangling and killing trees and you’ll often see where it has been cut at the base or removed from trees entirely. Now this is actually a myth, likely to have stemmed from the fact that if a tree is already dead / dying, the weight of ivy can lead to it falling. The plant itself doesn’t actually cause any harm to the tree at all and it is incredible for wildlife, with at least 50 species reliant on it.

Linked to saving the bees, ivy is one of the last plants to flower before winter sets in. Without ivy, many pollinators would be unable to feed up and be in good enough condition to survive winter. The bee in the photo (top right) is actually the Ivy Bee. Birds also get a good boost from the berries and shelter within the depths of the ivy, as do bats. It’s therefore well worth looking after your ivy where you can!

Myth 4 Brambles should be cut back (or should they?)

Most of us look at a dense tangle of brambles in horror as it creeps out, choking other plants. Clearing swathes of bramble to create space for nature is often a first step in a community project. But while we may not want to allow it to spread any further and lose grassland, should we hack it all back? Or could we be doing more harm than good? A nice stand of bramble like this, although a pain to work around, has numerous benefits for wildlife:

- Song thrushes would really suffer if big stands of brambles are removed – they love a nice dense bramble thicket for nesting in, to keep them safe from predators.

- The berries are important food for many birds and mammals, such as the adorable hazel dormouse, a European protected species. In late summer, you may also find fox or badger poo turned bright purple from all the berries they’re eating!

- The flowers provide nectar and pollen for many invertebrates.

- The dense structure and spiky stems create safe spaces for hedgehogs to shelter and move through and the jagged edges of thickets also create a nice microclimate for basking reptiles.

So it could well be worth keeping some of that bramble after all!

Myth 5 You have to plant seeds to get wildflowers (or do you?)

It’s not always as easy as you think to tell the difference between a natural and non-natural meadow. One of the problems we have when trying to establish natural meadows is that people have learnt to expect poppies and cornflowers and solid flowers from ‘wildflower meadows’, when really these are far from natural. A natural meadow will contain grasses and other species and you may need to look a bit closer to find the wildflowers, but the benefits to nature far outweigh those of the non-natural mixes.

If you do want to use these mixes, it is best to plant them in formal situations, to help people to understand that they’re not what they should expect of a natural meadow.

So do you have to plant seeds to get wildflowers? Well you do have to plant seeds to get something like the image on the left above, but not for the one on the right – that’s all about good management. Remember – a wildflower is a flower that grows in the wild, it was not intentionally seeded or planted. If you have a large area in which you’d like to see ‘wildflowers’, your best option is management and there are a few reasons why you should avoid planting seed mixes:

- Most of these seed mixes contain annual plants such as poppies, cornflowers etc. Whilst in theory, they should drop seed and replenish themselves, often the following year the display is much less impressive. Land managers then deploy big tanks of herbicide and scarifying machines and spray every native plant that has popped up in their place and scrape it back to earth again, before adding new seed mix. This is highly unsustainable in the long term!

- The brightly coloured species in annual seed mixes are non-native species to Wales, or even the UK! They can displace the distinctive native wildflowers already in the seed bank and erode the wonderful local distinctive wildflower diversity which we are lucky enough to have in Wales. Non-native species can even become highly invasive if introduced in the wrong place, causing a significant pressure to the local biodiversity.

- Many of our special pollinators are limited in range and specially adapted to feed from specific plants. Pollinators thrive on, and are best adapted to, flowers native to the same region. Introducing seed mixes containing non-native species can bring little to no benefit to the native pollinators.

Therefore, the best thing to do is to encourage the native seed bank to flourish through a change in management. This is the most sustainable method of increasing the area and extent of wildflower grasslands in your area. Consider cutting and removing the arisings once in March and again September, allowing the grass to grow between April and August. You will often be surprised by what pops up!

Rose Revera, Ecologist

Neath Port Talbot Council

With thanks to Mark Barber, Biodiversity Officer, Swansea Council